Rivian’s EV Factory Constrained by Chip Shortage

[ad_1]

[Stay on top of transportation news: Get TTNews in your inbox.]

Rivian Automotive Inc.’s “launch mode” is impressive — at least on its trucks.

While the battery-powered pickups go from 0 to 60 mph in 3.3 seconds, the 3.3 million-square-foot factory they roll out of is off to a protracted start. The assembly lines are perfectly capable of cruising speed; they just need more computer chips.

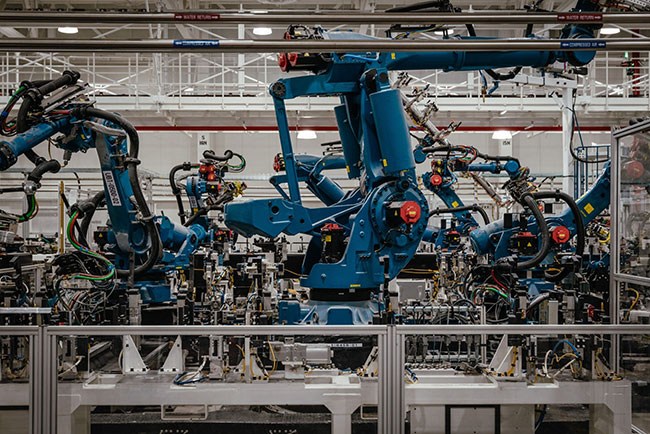

That was the message from CEO R.J. Scaringe last week as he took Bloomberg on a tour of the company’s Normal, Ill., plant two hours southwest of Chicago. The cavernous facility was packed with people — 5,200 in all, spread across different shifts. Industrial tools were punching metal into door frames and scores of robotic arms were welding body panels, smooshing on windshields and spraying paint.

Robotic arms on the assembly line at Rivian. (Jamie Kelter Davis/Bloomberg)

The parking lot behind the factory is crammed with hundreds of battery-electric pickups called R1T, Rivian’s debut consumer product. Parked alongside in trademark “Prime Blue” were dozens of plug-in commercial delivery vans for Amazon.com Inc., a critical customer and investor. All of the machines are awaiting shipment to their new owners, a dormant cavalcade ready to deploy in the coming electric vehicle wars.

Still, for all the activity, the factory is limping compared to rival facilities. Rivian forecasts it will run at just 50% capacity this year as a shortage of key parts constrains output. The assembly line was static in places and some workers were diligently organizing parts bins and rechecking machinery. At times, the first shift of the day files out at around 3 p.m., Scaringe said in an interview, simply because they don’t have enough to do.

“I would love to be in a position where we’re running two shifts, but two shifts would gain us nothing right now,” Scaringe said. “We need parts.”

Rivian is not an exception in the auto industry; it’s only different because it’s new. A few months ago, Rivian brought the first battery-powered electric pickup to the U.S. market, beating Tesla Inc., Ford Motor Co. and General Motors Co. in the process. The company counts Jeff Bezos and Amazon among its biggest investors (and customers) and its initial public offering in 2021 was the sixth-largest in U.S. history. But since the debut, shares have swooned and analysts have slashed projections and hopes for the stock.

Scaringe

Rivian has managed to speed the flow of certain products, in part by sending employees to supplier plants to step up the pressure. Computer chips, however, remain a challenge. There’s a fixed supply and typically chipmakers allocate them based on historic production, which is a huge disadvantage to a newcomer like Rivian. Scaringe says he spends much of his time calling chip executives and assuring them his factory is humming. Inviting a gaggle of reporters for a tour puts a nice underline on that missive.

“The allocation is being set based on whether they think we’re using the chips or not,” Scaringe said. “But it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy, because if Intel believes we’re not going to produce more than the next number, then that’s the number we’re going to produce.”

Scaringe reiterated a pledge that his factory will roll out 25,000 vehicles this year — including 10,000 vans Amazon is expecting, the first tranche of a 100,000-unit order to be completed by the end of this decade. That’s roughly half of what the plant would be capable of if it had a steady stream of parts.

The company has invested billions of dollars retrofitting a former Mitsubishi plant it acquired in 2017 for $16.5 million. Since then, the facility has expanded by 700,000 square feet. It’s now chockablock with tooling and machinery that takes months to map and install. One of Rivian’s biggest expenses to date, a state-of-the-art paint shop, is humming away like a wing of the Star Wars Death Star. Two assembly lines — one for the commercial van, the other for the company’s passenger pickup and SUV — weave around each other in a carefully choreographed industrial ballet. At one end of the plant, battery cells are packed into modules and joined with electric motors to form the “skateboards” which are bolted under all Rivian vehicles before they’re driven out of the facility to the parking lot outside.

Shout out to our team in Normal working hard to ramp production of the R1T, R1S and EDV. We produced 2,553 vehicles in the first quarter, and 3,568 since the start of production late last year. We’re excited about this progress, and especially to see more customer deliveries! pic.twitter.com/iy1HmS2CxA

— Rivian (@Rivian) April 5, 2022

Rivian is producing vehicles in batches: When enough parts pile up, managers crank up the conveyor belts and workers make a few dozen trucks. “We accumulate enough parts to build as fast as the plant can build,” Scaringe said, “but we can’t run like that for a week; we run through the parts so fast.” Eventually, Rivian plans for the facility to stamp out 200,000 machines a year by 2023. But so far, the factory’s limitations don’t appear to have had any effect on demand. Orders are coming in at an increasing rate, Scaringe said, as more of the trucks make their way into neighborhoods and parking lots. The high-profile IPO didn’t hurt either.

That presents its own set of challenges, however. With a wait list of more than 85,000, Rivian is selling hardware that customers won’t receive for nearly two years. Given that widening window, Rivian is about to change the way it takes orders, essentially uncoupling reservations from detailed prices. New customers will still be able to choose a truck, put down a deposit and claim a place in line, but they won’t be able to choose options — or configure their vehicle — and lock in a specific price until closer to an appointed delivery date.

“It’s a conversation we need to have,” Scaringe said. “Content is going to evolve, pricing is going to evolve; it allows those evolutions to occur without having to predict what they’re going to be precisely.”

The change will help Rivian account for inflation and fast fluctuating prices for commodities and parts. The company in early March walked back an announced price increase for people with standing orders when a swell of those customers canceled their reservations (although it maintained the higher stick price for new buyers). Also, Scaringe said, Rivian vehicles will change drastically in the next two years. They may look the same, but he says they will be more efficient, with improved charging speed and driving dynamics.

The R&D squad, in short, is working at a frenzy, even as the line workers wait for 10 or so parts out of 2,000 — each the size of a fingernail — which are holding up the process. “Layered on top of this is the question,” Scaringe said, “ ‘Is the plant actually not running and using the semiconductor shortage as an excuse?’ It’s really complex and it’s really frustrating.”

[ad_2]

Source link